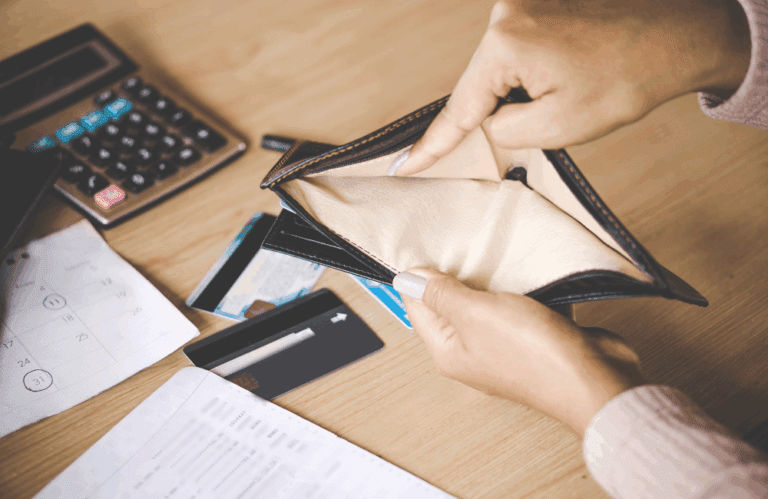

You’ve probably noticed it, if you’re paying attention. The small leaks. Not the dramatic kind that floods your life in one big surge, but the slow, annoying drip you keep meaning to patch up, someday.

A subscription you don’t use but can’t quite bring yourself to cancel.

The takeout order, placed not because you were craving it, but because choosing what to cook felt like one decision too many.

The premium shipping fee, because scrolling through delivery options required a focus you didn’t have left.

These are the prices you pay when ADHD is in the driver’s seat. They’re the price of running out of deciding.

No time to read? Here are the key takeaways:

- ADHD leads to decision fatigue, causing even small choices to feel overwhelming and expensive.

- Small expenses accumulate as you avoid making decisions, ultimately costing more money.

- Daily financial decisions can deplete mental energy, making it harder to manage money effectively.

- Systems meant to help with budgeting can become sources of additional stress, adding to decision fatigue.

- Removing low-value decisions can improve financial clarity and reduce the toll of decision fatigue.

Why ADHD Makes Every Financial Decision Cost More

Most conversations about money and ADHD focus on impulse control, as if the problem were simply wanting things too much.

But there’s another pattern, quieter and harder to name. It’s what happens when the act of choosing itself becomes so depleting that paying extra starts to feel like relief. When spending money becomes the path of least resistance because you’re already carrying too many choices that never got made.

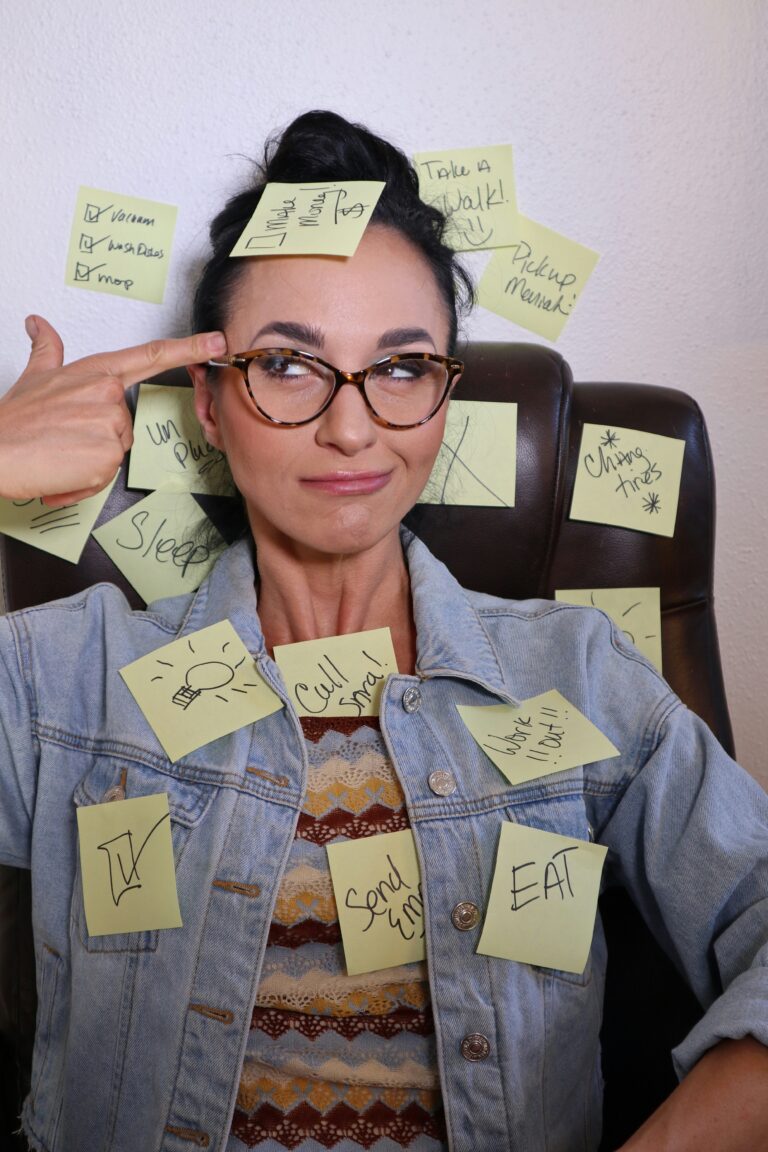

How many decisions have you postponed today?

Not the big ones with clear stakes and visible consequences, but the accumulating minor ones.

Which insurance plan? Whether to switch phone providers. If that gym membership still makes sense. Whether to return the thing that doesn’t quite fit.

Each one is small enough to defer, significant enough to linger, too numerous to escape.

The cognitive load doesn’t necessarily stem from the decision itself. But from holding all the unmade ones simultaneously. Your brain knows they’re there. It’s tracking them, even when you’re not consciously thinking about them.

And tracking requires energy that sleep will not replenish. So, what happens to your capacity for financial clarity when your attention is already allocated before the day begins?

When the mental budget for decisions is spent before you’ve looked at the actual budget, where does discernment go?

The Hidden ADHD Tax You’re Paying Daily

You know that feeling at the end of the day when someone asks where you want to eat and you genuinely can’t answer? That’s because choosing what to have for dinner and choosing whether to refinance your student loans draw from the same reservoir.

Your brain is one of the most metabolically expensive organs in your body—it burns about 20% of your total energy even when you’re doing nothing. And when it comes to decision-making, it doesn’t distinguish between trivial and consequential.

Choosing what to have for dinner costs the same as choosing whether to refinance your student loans.

A decision is a decision.

And when the reservoir runs dry, something has to give. Usually, it’s the decisions that would save you money.

The person who has already made forty micro-decisions before lunch is not operating with the same discernment as the person who hasn’t.

And our financial obligations, with its endless choices, its optimized friction, its monthly billing cycles designed to be just forgettable enough, knows this.

Your ADHD brain is not inherently bad with money; it’s succeeding at decision management in an environment that generates decisions faster than your nervous system was designed to process them.

The ADHD brain, already working harder to filter signal from noise, to prioritize without a built-in hierarchy, to remember what was supposed to happen when, runs out of deciding sooner. It’s burning fuel at a different rate in a world that demands constant choosing.

Why Impulse Spending Isn’t Always About Impulse

Consider what we already know about our own behavior patterns. The decisions we make well are usually the ones we’ve made automatic. The bills on autopay never accrue late fees, for the most part. The recurring grocery order prevents the exhausted evening pantry stare. The morning routine that requires no choices gets executed even on hard days. Think brushing your teeth in the morning. When a decision stops being a decision, it stops depleting you.

The small purchases made from depletion add up differently from the ones made from desire. Instead of being about wanting, they’re about ending.

Ending the back-and-forth, the comparison and ing the mental tabs open for weeks. The money spent is often less about acquiring something and more about resolving the cognitive dissonance of the unmade choice.

When Your Financial System Becomes Another Source of Depletion

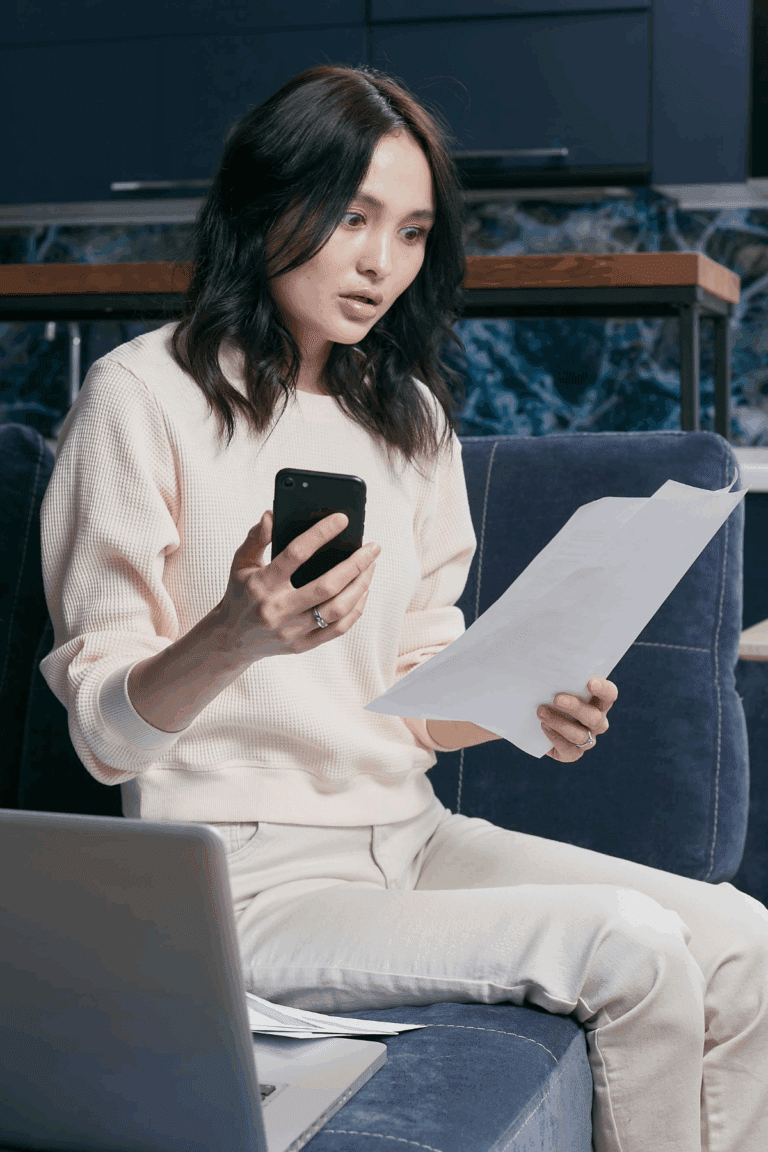

You’ve probably tried budgeting. More detailed spreadsheets. Clearer financial goals. And they helped, maybe, until the system itself became another thing requiring decisions.

Another set of categories to maintain. Another layer of choice about how to track the choices about how to spend the money earned by making choices all day at work.

At some point, the organizational system designed to create clarity becomes its own source of depletion by adding decisions to a life that’s already full of them.

The question isn’t whether the system is good. The question is whether you have the bandwidth to operate it. And on the days you don’t, what happens to your money then?

That’s why you order Uber Eats because just thinking about meal planning makes you want to crawl under a blanket. Or kept paying for that meditation app because, somehow, those three clicks to cancel always seem like too much.

The higher insurance premium you’re still paying because comparing plans requires a kind of sustained attention you haven’t had in months. The late fee from the bill you meant to pay, but first you had to log in, and then you had to find the account number, and by then, something else needed your attention.

None of these is catastrophic alone. But they compound. The invisible tax of operating in a state of perpetual decision saturation.

What Changes When You Stop Trying to Decide Better

The real financial cost of ADHD isn’t the impulsive purchase, but the thousand tiny decisions that never get made efficiently enough to prevent the slow leak.

You can’t think your way out of decision fatigue. Awareness doesn’t restore bandwidth. Knowing why you’re depleted doesn’t un-deplete you. Understanding the mechanism doesn’t change the math. You can’t decide your way into having fewer decisions.

So what actually changes it?

- Something has to stop being optional.

- Something has to be chosen once and then protected from being re-chosen.

- Something has to move from the open-loop pile to the closed-loop pile, through a structure that makes deciding unnecessary.

The question isn’t what you should do. The question is what you’re willing to stop deciding about.

What would your financial life look like if the decisions that drain you most were simply… removed?

Not solved. Not optimized. Not managed better. Just removed from the daily menu of things requiring your finite capacity to choose. Money Blocks™ is a financial clarity framework, inside the Permission To Achieve™ System, designed to remove daily money decisions before they create depletion.

The expensive part of ADHD isn’t the diagnosis or the medication or even the occasional impulsive purchase. It’s the ongoing cost of operating without the structure that would make most of your financial life automatic.

Having endless financial options is exhausting and actually hurts you. What you need is a simple, clear plan with a few basic rules. Your money doesn’t need constant tinkering; it just needs fewer, better decisions.